“The interest in farming and working with farmers has always been part of me, I understand it very well because I grew up as a farmer and now, I am a farmer. It’s calling for me to work with farmers.”

Jeko Manata grew up in southern Zimbabwe, surrounded by agriculture and with a family background in the field, it’s no surprise that the interest in farming and working with farmers has always been a part of Jeko. His father was an extension worker in government and his mother was a small-scale farmer, and through his upbringing he has come to understand and appreciate the importance of good quality seeds for farmers.

“For farmers to collaborate with breeders is something that we never dreamed about in the early days.”

At the time, most seeds in Zimbabwe came from a large seed company named Seedco. Or at least what Jeko knew as seeds, meaning commercial seeds. He explains that all the seeds grown by his mother were not valued as highly as the Seedco seeds. Only later did he understand the importance of these homegrown seeds and realized that they have always been there. Jeko works to see farmers’ lives transformed, for them to independently have their own good quality seeds. He does this through the Community Technology Development Trust in Zimbabwe (CTDT).

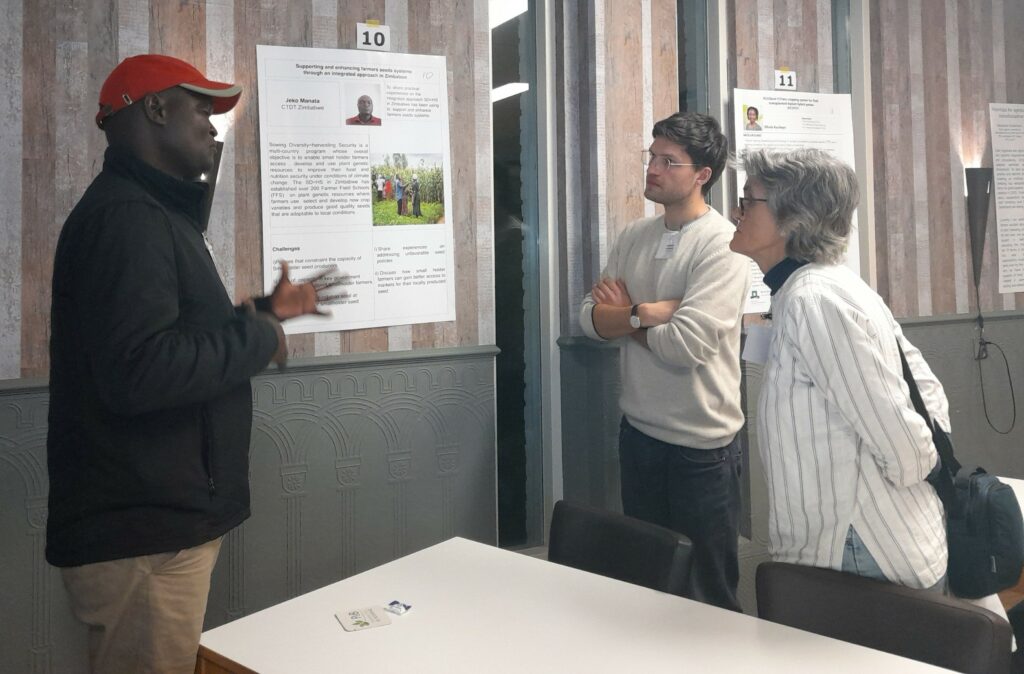

As part of a delegation of Sowing Diversity=Harvesting Security, Jeko Manata participated in a week-long course on Smallholder Engagement in Seed System. Developed in a coalition made of Wageningen University, the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, the Production Ecology & Resource Conservation and Oxfam Novib through the Sowing Diversity=Harvesting Security program (SD=HS).

“It was a real opportunity for me as a practitioner working in Africa with farmers. It was an occasion to try and marry their theories and concept with our experience in practice and find where we can work together.”

Jeko shares that this was a rare opportunity for practitioners to meet with professors and discuss the same issues they face on the ground. Despite being intimidated by the academic participants and respected professors in this field, Manata soon gained confidence and realized that his work with Sowing Diversity=Harvesting Security is highly relevant and recognized by institutions like Wageningen.

Throughout the course, Jeko was impressed by the group’s engagement and thoughtful consideration of the cases presented. The group was able to identify both positive aspects and areas for improvement, and it became clear that there was much to be gained from continued exchange between practitioners and academics. He goes back to Zimbabwe with much on his mind, and discussions to be had back in Zimbabwe with his colleagues at CTDT.

“We must involve farmers, just like we were involved in this postgraduate course.”

Manata left the course with a deep appreciation for the importance of critical reflection and taking time to take a step back to deeply reflect. Translating this to the SD=HS program would mean involving farmers in the planning process, so they can directly contribute to the program. The CTDT participant was particularly inspired by a presentation on methods, and how the choice of methods will influence the outcome. For him, this made the case for farmers full participation once more. Overall, Manata believes that involving farmers in both the academic and practical aspects of seed systems will lead to better outcomes and more sustainable solutions.

“We both learned how we can work together, as scientists and practitioners. I think we filled some of the gap, so that their theories are grounded in reality.”

Jeko firmly believes academics also learned from the practitioners. In terms of practical experiences and how theories land on the ground. He hopes to continue this exchange and encourages doctoral students to include practical on-the-ground issues in their research. By working together and involving all stakeholders, we can continue to improve seed systems and transform the lives of farmers!